Photo via The Globe and Mail

Background on Toronto Community Housing

Toronto has been a forest of cranes for the past few decades, with rapid growth in its core neighbourhoods transforming both the city’s skyline and residential character. After a nineties-era downturn in the property market, rising house and land values and a development-friendly environment led to the construction of over 200,000 condominium units between 2000 and 2017.

The benefits of all this construction have been unevenly distributed. Canada has few publicly-funded housing supports, and lacks major programs to incentivize private-market construction of affordable housing. Toronto itself has no inclusionary zoning, in-lieu fees, or affordable unit production mandates, meaning that the vast majority of units built have been market-rate. In 2018, Demographia ranked the city the 5th-most-expensive major housing market in the world.

A lucky few lower-income residents may find an affordable home in the city’s roughly 120,000 units of subsidized housing stock.1Page 39, Toronto Housing Market Analysis Roughly 60,000 units are owned and managed by the Toronto Community Housing Corporation, North America’s second-largest public housing agency by number of units after NYCHA. Much like its American counterparts, TCHC is struggling after decades of disinvestment. As of 2017, it faced a serious $1.6B repair and capital investment backlog.

CityPlace Block 32 Project Overview

Despite its structural issues, TCHC has found ways to benefit from the intense condo-centric development ecosystem in the city, working with private developers to rebuild social housing complexes and build brand-new affordable units elsewhere. TCHC’s CityPlace Block 32 project exemplifies the latter approach: an attractive high-rise building with modern amenities that blends into a neighbourhood of market-rate residential towers.

As built, Block 32 consists of 427 units spread across three connected buildings with distinct entrances:

- 150 Dan Leckie Way, a 41-storey steel-and-concrete tower

- 146 Fort York Boulevard, a 9-storey steel-and-concrete building and the southern half of the podium

- 125 Queen’s Wharf Road, an 11-storey steel-and-concrete building and the northern half of the podium

Furthermore, around the building’s perimeter, 34 at-grade townhouse units have their own entrances.

Of the building’s 518,627 SF of gross indoor floor area:

- 504,182 SF is residential

- 7,330 SF is indoor amenity space, including a community hall for meetings and social events, a community kitchen, a billiards and multi-purpose game room, a gardening room, and three laundry rooms—the largest one overlooking the outdoors

- 7,115 SF is ground-floor retail, divided into 5 spaces; the largest is leased to Tim Horton’s, a fast food/coffee chain, with the remaining 4 leased at minimal cost to the Toronto Arts Council until 2020 to comply with city public art requirements

There is an additional 21,690 SF of outdoor amenity space, including rooftop community planters and an outdoor terrace with communal barbecues. However, the amenity spaces may have been too plentiful; TCHC notes that they were “over-designed” and that they faced “a challenge to manage the variety of amenities,” with the property manager “significantly restrict[ing] access.”2Page 5, Block 32 Project Completion Report Still, the amenity-rich site is worth noting.

Neighbourhood Context

Block 32 began as a parcel of land in a disused railyard near the city’s downtown core and primary transit hub; in 1994, the city dedicated it for future affordable housing construction. The rest of the railyard has since been transformed into CityPlace, a collection of high-rise condos organized around public amenities, including the Fort York Historical Site, a Toronto Public Library branch, and Canoe Landing Park. A public school complex is being built.

CityPlace is fairly well-served by public transit, including the Bathurst, Harbourfront, and Spadina streetcar lines. The Gardiner Expressway, a major thoroughfare, passes through the area.

Block 32 is adjacent to a pedestrian bridge that connects the neighbourhood to King West, an office, retail, and entertainment district across the rail corridor to the north. Further east on Front Street, Toronto’s Financial District is one of its densest employment areas. Union Station, the city’s main commuter and intercity train station, is at its centre. Tourist and sporting venues are nearby. South is the Billy Bishop airport on Toronto Island, across the water from the Harbourfront cultural and park district.

The broader neighbourhood has a reputation as a rental-dominated area full of younger professionals, who tend to move out in later life stages given small units. Streets are dominated by chain retail, including grocery stores.

Design and Features

At the core of the building’s design is its target population: families. Unlike most of the towers surrounding Block 32, over 50% of its units have 3 or more bedrooms, with an average unit size in the building over 1,100 SF.3Page 5, Block 32 Project Completion Report

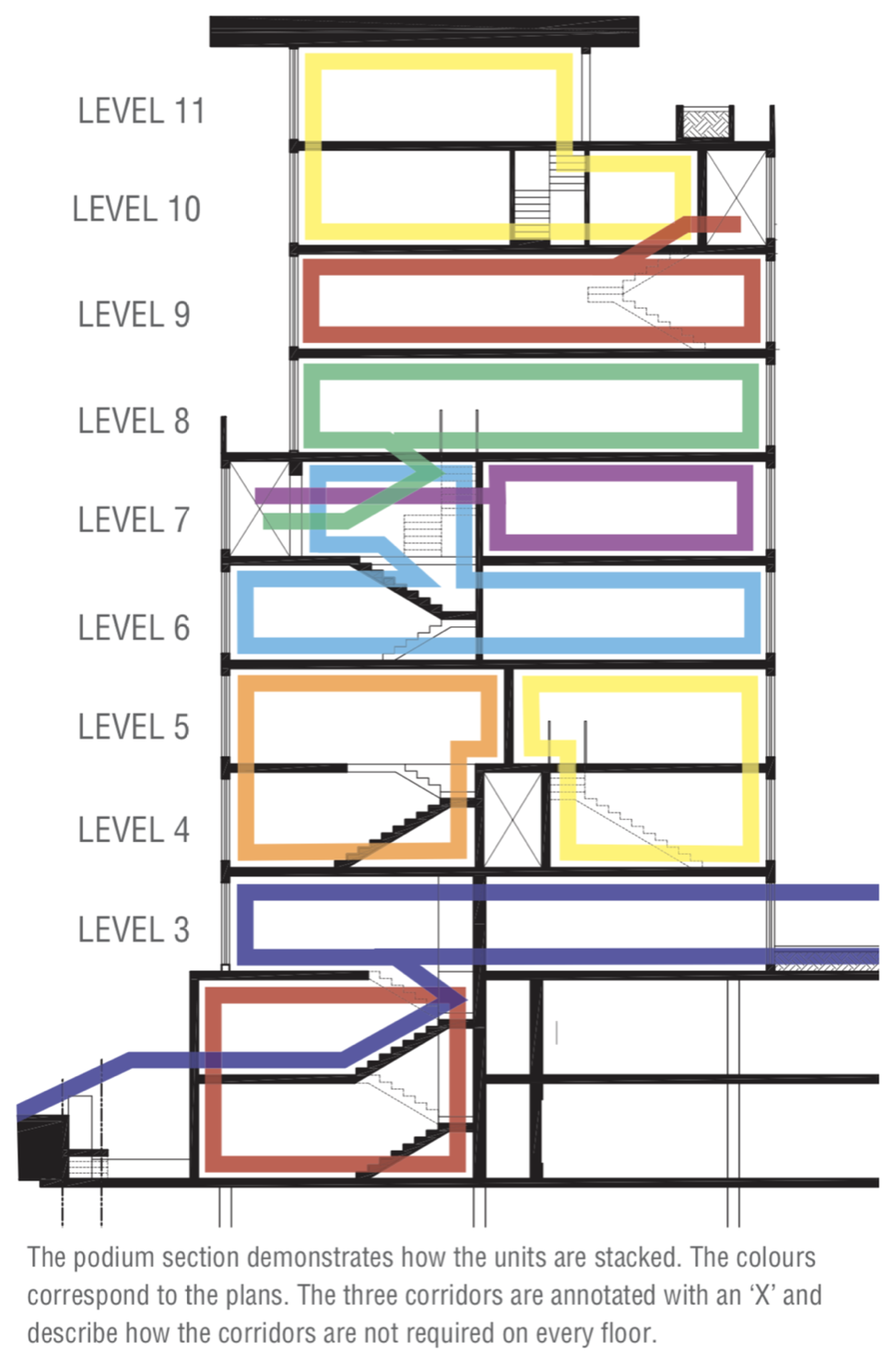

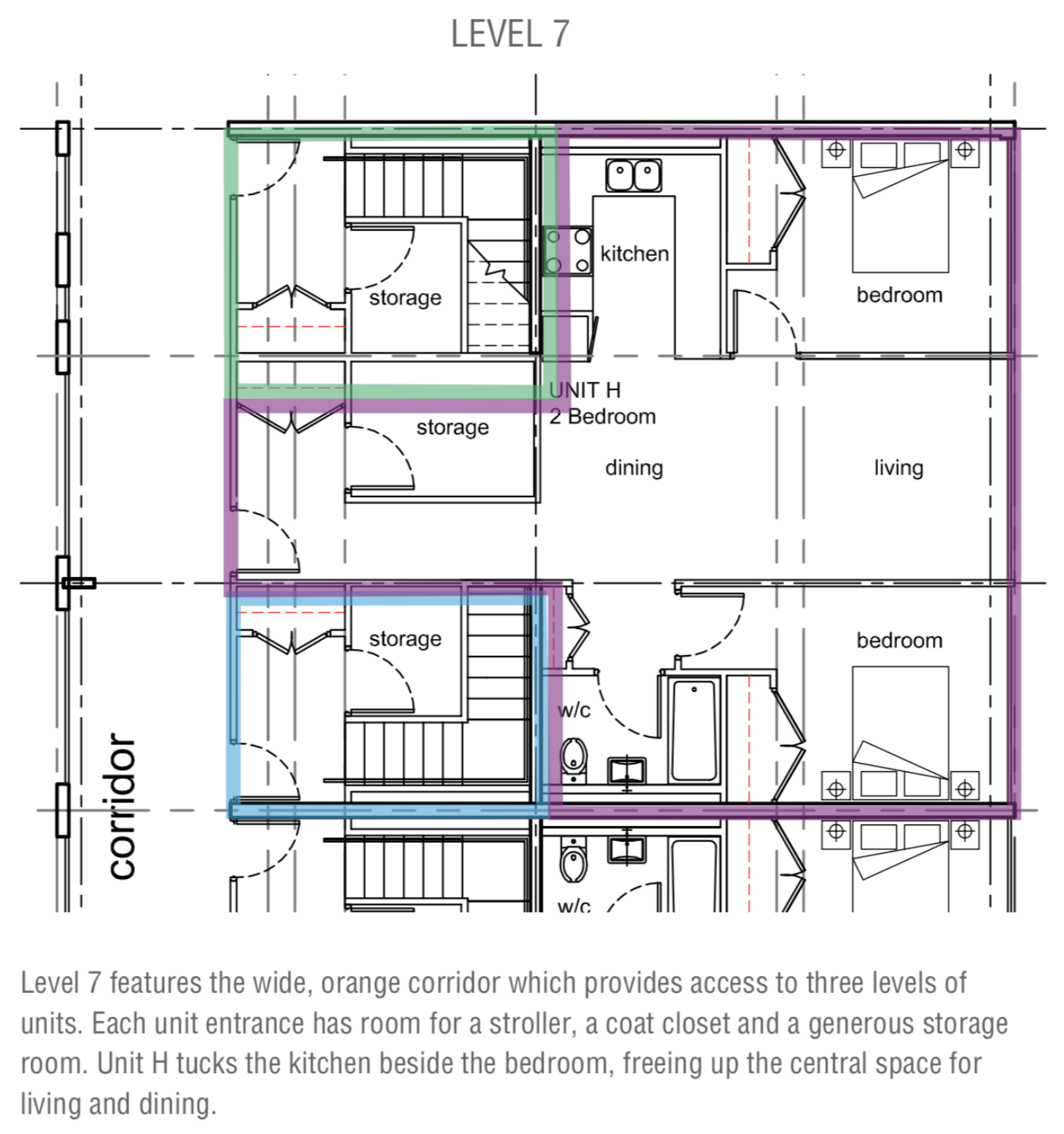

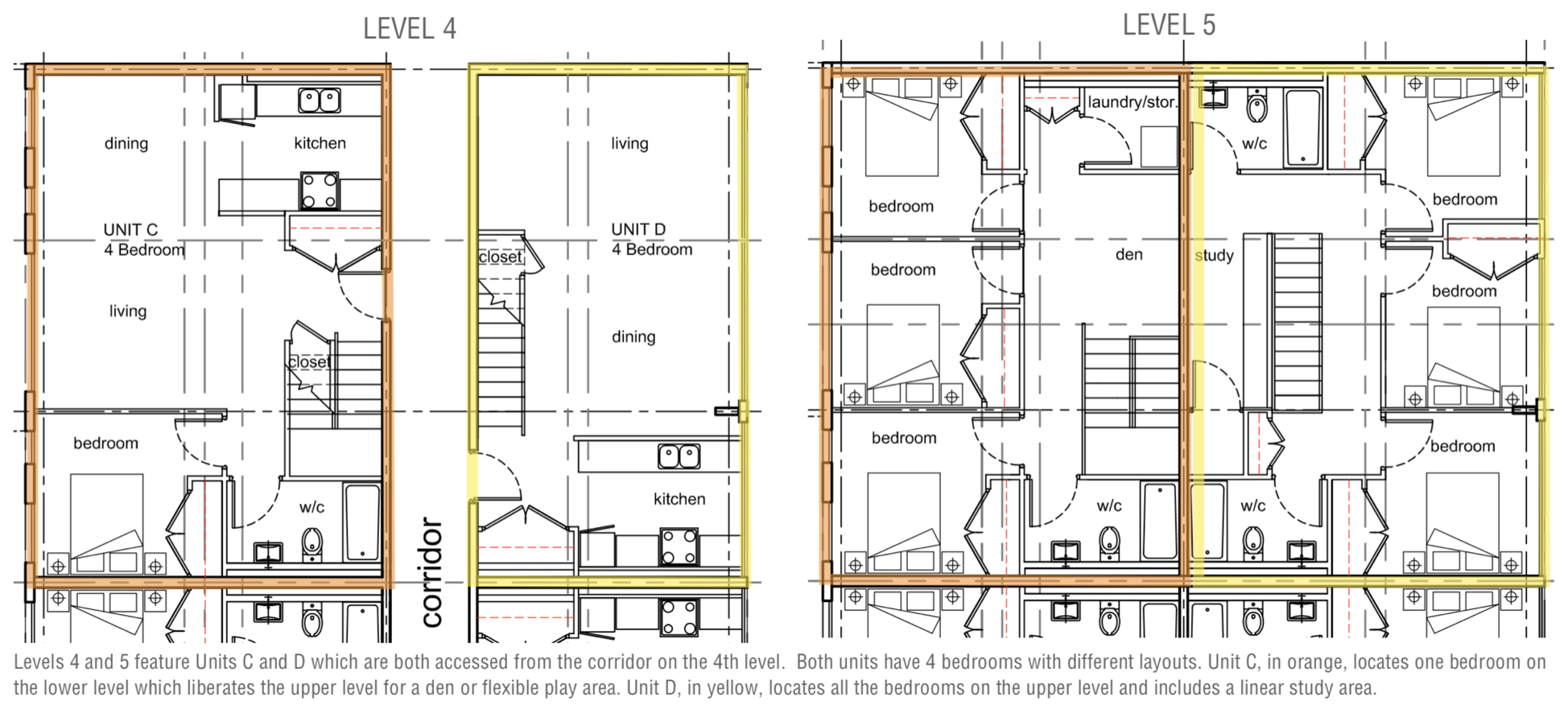

Many units are spread over two floors. In the podium, they are stacked to minimize the number of corridors required, as the section illustrates. This creates busier, more community-oriented hallways. The bright-orange 7th-floor corridor feeds three different levels of units, maximizing “eyes on the street” and collective exposure.

Common areas and amenities are centralized on the first floor of the building, maximizing outdoor views and access to all residents.

With units ranging from one to five bedrooms, format and layouts vary. Most embed a large foyer and storage space at the entry, helping define a unit.

TCHC does not make building-wide designs publicly available, but a City of Toronto case study on Block 32 shows the typical configurations of several podium units, as they relate to one another and the corridors.

The colours of the unit outlines correspond to their position in the section.

With LEED Gold certification, the building is home to numerous sustainable design features, including:

- 40% lower energy cost compared to code standards

- 50% of roof area dedicated to either green plantings or rooftop gardens

- Rainwater collection system to irrigate courtyard and street level planters

- Water-saving plumbing fixtures

- Ground-source heat/cooling pump for the full building and heat recovery units in each dwelling unit

- Energy-efficient lighting fixtures

- Energy Star appliances

- A three-chute garbage system for waste diversion4Page 10, Block 32 Project Completion Report

Design was led by KPMB Architects, in association with architects of record Page + Steele/IBI Group. Shirley Blumberg, a partner at KPMB, led the team.

Development Process

Block 32 is a steel-frame concrete high-rise. The development manager was Context Development, and the construction manager was Bluescape. The project was delivered ahead of schedule and under budget.

CityPlace, a new development surrounded by traditionally industrial areas, did not attract the same degree of neighbourhood scrutiny or resistance as a project might in North Berkeley. Block 32, its affordable component, did not attract meaningful media or public attention until it was completed.

Costs and Funding

The project cost CA$104M to deliver, with hard costs representing $88M of that total. Block 32 attracted CA$112M in funding; $59M from a TCHC bond, $36M in grants from all three levels of government (the City of Toronto, the Province of Ontario, and the Government of Canada), a land gift worth $8M, and a 55% share of profits from the adjacent market-rate development worth $9M. At completion, the project left $8M in cash on TCHC’s balance sheet.

94% of TCHC’s $601M 2019 operating budget comes from rent paid by tenants ($319M) and subsidies from the city and provincial government ($243M).5Page 18, TCHC 2019 Budget

Program and Management

Block 32 has both RGI and affordable rental units, representing the two distinct cost models TCHC administers:

- 32% of units are RGI, rent-geared-to-income, in which residents pay 30% of household income per month in rent

- 68% of units are affordable rentals, meaning that the city charges a flat rent amount, and limits occupancy to those with monthly household incomes no higher than 4 times the monthly rent amount

Toronto does not place any restrictions on maximum income for RGI units, and sets a minimum rent of $85/month. In practice, low-income people are the main beneficiaries, and a 10+ year waiting list means that most people turn to the market to find housing.

For the affordable rental units in the building, rents must be set between 80-100% of “average market rent”—ranging from $1,016-$2,185/month, based on unit size. This means the maximum income ranges from $49K for a low-priced 1-bedroom to $104K for a full-priced 5-bedroom unit. Toronto’s median income was $78K in 2015. This suggests resident incomes range from 0% to 130% of the city’s median.

Family size influences available unit types, with 2 spouses (or a single parent and child) to share a bedroom, plus 2 children per bedroom for 2-and-3-bedroom units or 3 children per bedroom for 4-and-5-bedroom units.

There are few restrictions on eligibility.6See this page on RGI in Toronto and this TCHC primer on eligibility. Legal Canadian residents who don’t owe rent to a social housing provider, don’t have convictions related specifically to rent payment, and don’t own livable houses are eligible.

TCHC owns the building, and contracts with Greenwin Inc. to manage the property. The property manager runs the day-to-day operations and provides amenity programming, which is apparently limited, per the notes above.

Successes

- Block 32 represents the future of social housing in Canada—new-built units with forward-thinking, highly sustainable design.

- High-rise construction allowed for significant unit production in a dense, high-cost area, close to transit and major employment centres.

- The project won accolades for its family-centric designs.

- While 89% of TCHC’s units are RGI, Block 32 is a test case for a majority (68%) affordable-rental building, reducing some of the financial barriers to ongoing maintenance.

- Despite the high overall cost ($104M), the large number of units produced means per-unit costs are ~$245K, and ~$204/SF of residential/amenity area.

- The building, unsurprisingly, was fully occupied almost immediately. By all accounts, residents are satisfied, and the families the units were built for are using them to their full advantage.

Challenges

- Setting rents with TCHC’s “affordable” scheme excludes many of its lowest-income tenants.

- Over-production of amenities has created issues for both residents and property management.

- TCHC specifically noted that the building’s scale and design—especially its three separate entrances—may prove unwieldy in the future, and recommended focusing on sub-200 unit buildings to concentrate management on more central areas.

- The reality is that budgetary constraints will keep TCHC and most of its housing far behind Block 32.

- Even with Block 32 full, there’s still too little affordable housing in CityPlace.

Takeaways

- In an ideal world, all social housing would be built from scratch in a well-integrated community with plenty of amenities and easy access to jobs and transit. This is, needless to say, easier said than done.

- Building social housing for families should take into consideration the real needs of a family on a day-to-day basis, like Block 32 has done. Creating places to watch kids play as you fold laundry. Ensuring adequate storage and friendly layouts. Finding ways to stitch together building community.

- Thinking ahead—wayyyy ahead—when it comes to setting aside land for affordable housing can really pay off. Embedding it in broader development agreements, as Toronto did with CityPlace, can pay real dividends.

Appendix A: Unit Mix Table

Image Credits

- Drawing of Block 32 from UrbanToronto

- Photos in Project Overview: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6

- Photos in Design and Features: 1, 2

- Water recapture diagram

- Site layout diagram