Prepared by Gary Gerbrandt • CP 200/Professor Stephen Collier • December 7, 2018

Toronto’s waterfront is enjoying a decades-long period of reinvestment, as it transitions from a hodgepodge of once-industrial brownfield lots to an eastern extension of the city core’s gleaming skyline. Left mostly vacant in the wake of deindustrialization, the area has begun to transform into a community of condominiums and offices. Rapidly rising land values citywide, and a paucity of land near jobs and transit in the city’s core neighbourhoods, pushed developers and planners to take their hammers and pencils to the shores of Lake Ontario.

Exploring the new neighbourhood, you can’t help but feel excited for this dawning phase in the waterfront’s history. People are moving in to new condos built along the sharp lines of the filled land’s concrete retaining walls, with beautiful new parks and a multimodal street that will someday host a light rail line alongside its separated bike lanes. Sidewalk Toronto, perhaps the splashiest urban development in the world today, has announced its plans to turn the undeveloped Quayside parcel into a playground of forward-thinking tech-urbanist ideas. The Alphabet company’s vision has been controversial—particularly given its proposal for mass data collection on its inhabitants’ behaviour—but the city’s enthusiasm for waterfront development will likely mean that its proposed tall-timber buildings will find their footing in the near future.

Looking southeast from the foot of an immense abandoned soya silo on the Quayside property, one can see the true scale of Sidewalk’s, and Toronto’s, ambition. Toronto’s Port Lands stretch east from Quayside, projecting into the lake across the Keating Channel at the mouth of the Don River. Sidewalk aspires to extend its successes at the 12-acre Quayside site to the sprawling 800 acres of former industrial properties—“one of North America’s largest areas of underdeveloped urban land,”1“Sidewalk Toronto,” Sidewalk Labs, accessed December 7, 2018, https://sidewalktoronto.ca/. as the project’s website puts it. No matter their developer, the Port Lands are the largest piece of Toronto’s near-future growth plans, and the most untouched.

A century ago, though, the Port Lands were truly untouched—they didn’t exist. The story of what came before, what’s being done now to remake them, and governments’ prioritization of planning and funding for the area is another chapter in Canada’s long history of environmental destruction and anti-Indigenous colonial systemic violence. One of the critical parts of governmental plans to unlock the Port Lands for development is the creation of Villiers Island, a verdant jewel of a park that will partly restore a marsh at the Don’s mouth, surrounding a collection of new residential and commercial developments.2John Rieti, “Toronto’s Port Lands Plan Includes Building a New Island,” CBC News, July 2, 2017, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/port-lands-development-1.4187182. Pursued in the guise of environmental restoration and flood protection as climate resilience planning, Villiers Island is at its core an economic calculation wrapped in an environmental amenity, opening new land for Toronto’s developers. In a province and country where environmental justice and Indigenous rights are among governments’ lowest priorities, the investment in the environment of the unpopulated Port Lands speaks volumes.

When European settlers began to populate the shores of Lake Ontario in what is now Toronto, they were greeted by an enormous ecological spectacle. Sarah Ashbridge, a Quaker and British-allied political refugee, escaped American political persecution by boat with her family in 1793. As they sailed past a large marsh to the east of the town’s harbour, someone aboard blew a shell horn; the Ashbridges watched in awe as thousands of ducks alighted from the trees and reeds at the sound.3“Timeline: Ashbridge’s Bay,” Leslieville Historical Society, accessed December 7, 2018, https://leslievillehistory.com/timeline-ashbridges-bay/#_ftnref18. Almost 1,300 acres of wetlands, crisscrossed by channels and dotted with ponds, the marsh served as a porous mouth for the Don River. It surrounded a shallow bay of water, sandwiched between the shoreline and a large sand spit formed by the river’s annual silt flows.4Jennifer Bonnell, “Ashbridge’s Bay,” Don Valley Historical Mapping Project, published 2009, accessed December 7, 2018, https://maps.library.utoronto.ca/dvhmp/ashbridges-bay.html. The Ashbridges were granted a large plot of land on the eastern shores of the city, and soon became part of the early Toronto elite; the marshy body of water at the edge of their property was christened Ashbridge’s Bay in their honour.5“Ashbridges Bay Park,” City of Toronto, accessed December 7, 2018, https://www.toronto.ca/data/parks/prd/facilities/complex/1/index.html.

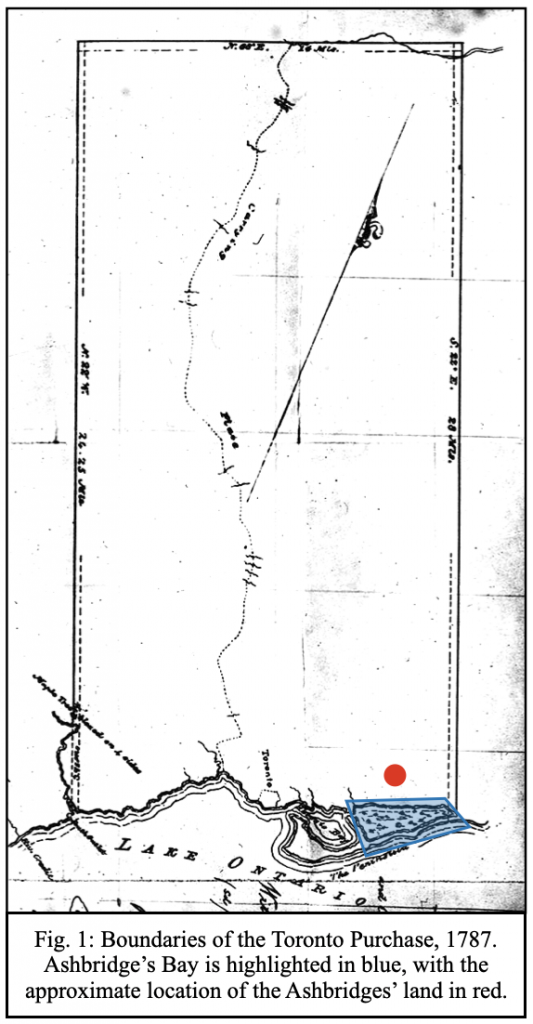

The land given to the Ashbridges was a direct redistribution of natural wealth from local Indigenous peoples to Europeans, in the first example of economic colonialism in the history of the Port Lands. For centuries prior to British settlement in Toronto, southern Ontario was the homeland of the Mississaugas, a large group of Anishnaabeg First Nations peoples.6Wayne Roberts, “Whose Land?” NOW Magazine, July 11, 2013, https://nowtoronto.com/news/whose-land/. As the American Revolution wound down, the British Crown forcefully purchased Mississauga land in southern Ontario to give as large grants to Loyalist families as a way to keep them in North America as British subjects.7“The Mississaugas,” Heritage Mississauga, accessed December 7, 2018, http://heritagemississauga.com/the-mississaugas/. The Toronto Purchase of 1787 (see Fig. 1, below) was an unequal treaty which resulted in the transfer of essentially all of present Toronto to the British Crown;8“Toronto Purchase,” Mississaugas of the New Credit First Nation, accessed December 7, 2018, http://mncfn.ca/about-mncfn/land-and-water-claims/toronto-purchase/. the eastern boundary of the original map falls roughly at the edge of Ashbridge’s Bay, encompassing the family estate.

Sources that describe the Mississaugas’ interactions with Ashbridge’s Bay are limited, but settler accounts from the late 18th century suggest that the marsh served as a spiritual and economic resource. Early maps indicate “Indian huts” and a portage near the shoreline, suggesting established settlement.9“Timeline: Ashbridge’s Bay,” https://leslievillehistory.com/timeline-ashbridges-bay/#_ftnref16. An 1805 account noted that the “peninsula affords a most delightful walk or ride, & is considered as so healthy by the Indians, that they frequently resort to it when indisposed.”10“Timeline: Ashbridge’s Bay,” https://leslievillehistory.com/timeline-ashbridges-bay/#_ftnref24. A diary entry from January 1794 describes Mississaugas ice-fishing on the marsh;11“Timeline: Ashbridge’s Bay,” https://leslievillehistory.com/timeline-ashbridges-bay/#_ftnref19. by 1810, they had begun to commercialize the fishery, selling the catch near the central St. Lawrence Market.12 “Timeline: Ashbridge’s Bay,” https://leslievillehistory.com/timeline-ashbridges-bay/#_ftnref29.

Meanwhile, the economies of European settlement began to encroach on Ashbridge’s Bay Marsh. In the early days, dense settlement by water meant that malaria became common, with settlers often blaming the marsh. But Europeans also saw the marsh as a hotbed of economic opportunity—when transformed. As contemporary memoirist Henry Scadding later summarized:

The language of the early Provincial Gazetteer, published by authority, is as follows: “The Don empties itself into the harbour, a little above the Town, running through a marsh, which when drained, will afford most beautiful & fruitful meadows.” In the early manuscript Plans, the same sanguine opinion is recorded, in regard to the morasses in this locality. On one, of 1810, now before us, we have the inscription: “Natural Meadow which may be mown.” On another the legend runs: “Large Marsh, & will in time make good Meadows.” On a third it is: “Large Marsh & Good Grass.”13“Timeline: Ashbridge’s Bay,” https://leslievillehistory.com/timeline-ashbridges-bay/#_ftnref27.

The inevitability of this language is striking—that the marsh itself would be a future meadow seems almost to go without saying. Ecocultural historian Rod Giblett, in an article about the city’s relationship to the marsh, notes that there is a default mindset that wetlands generally are unhealthy and backward places—and that “psychogeopathology” motivates their masters to “fill, dredge, drain or reclaim” them.14Rod Giblett, “A City ‘Set in Malarial Lakeside Swamps’: Toronto and Ashbridge’s Bay Marsh,” TOPIA: Canadian Journal of Cultural Studies 29 (2013): 106, 114-115. Yet this early push to convert the marsh into land that met a contemporary European colonial mindset of productivity—that is, blatantly ignoring the Mississaugas’ fishery and significant environmental benefits of a wetland—did not bear fruit.

Instead, it was Toronto’s growth over the ensuing decades that killed Ashbridge’s Bay and led to the creation of the Port Lands. With so many rivers running through the city—the Don, Humber, and Rouge are the largest—there was little impetus to invest in sewage infrastructure. The city’s residents and businesses dumped raw sewage and refuse into the rivers. With the city’s population concentrated around the Don, it quickly became polluted. The marshlands of Ashbridge’s Bay, as a primary outlet for the Don, became overwhelmed with garbage and human and animal waste.15Giblett, 115.

At the same time, an industrial economy was flourishing in the city. Founded in 1832, Gooderham & Worts was one of Toronto’s early industrial success stories. What started as a windmill on the Lake Ontario waterfront became an integrated distillery business; by 1877, the limestone building at its core was the anchor of the world’s largest distillery. Later abandoned, those facilities are now the centre of the Distillery District—one of the first redevelopments of the waterfront’s industrial lands, built in the early 2000s.16Tracy Hanes, “Spirits Rising at the Old Distillery,” The Toronto Star, June 23, 2007, https://www.thestar.com/news/2007/06/23/spirits_rising_at_the_old_distillery.html. The firm made the most of its production process, branching out into the beef business as a way to dispose of its spent grain mash. At first, the company fattened cattle on the mash in what is now the urban core; in 1866, their feedlots were moved to a larger plot of land east of the Don River, on Ashbridge’s Bay.17“Chronology of the Distillery Historic District,” Distillery District Heritage, accessed December 7, 2018, http://www.distilleryheritage.com/PDFs/chronology.pdf. By the late 1880s, their feedlots at the marsh edge had grown to a capacity of 4,000 cattle, with no treatment facilities for their manure.18Gene Desfor, “Planning Urban Waterfront Industrial Districts: Toronto’s Ashbridge’s Bay, 1889-1910,” Urban History Review 17, no. 2 (1988): 80. About 80,000 gallons of manure poured into the marsh every day.19Bonnell, “Ashbridge’s Bay,” https://maps.library.utoronto.ca/dvhmp/ashbridges-bay.html.

By 1853, health concerns about the marsh had shifted away from malaria; a proposal to drain and fill part of the marsh by city council member and engineer Kivas Tully cited the avoidance of cholera as a key aim.20Desfor, 79-80. In 1882, Ashbridge’s Bay was so polluted that garbage seeping into the harbour presented difficulties for marine navigation. The city built a breakwater to keep the filth confined to the cesspool, but by the end of the decade, the breakwater had cut off outlet flows for the marsh, seriously worsening the water conditions.21Desfor, 80. On any given day, a retching spectator could have detected the various odours of human sewage, cow manure, and garbage, in addition to industrial waste—offal from abattoirs and chemicals from refineries.22Giblett, 115.

Toronto’s economic transformation, and its environmental consequences, shaped both perceptions and realities of the marsh. First, an economic transition forced out the original Mississauga users of the marsh, in favour of European colonists. Settlers saw it as a potentially productive site, albeit after severe environmental destruction; less than fifty years later, thanks to a different kind of environmental destruction, it was seen as a health problem that the city had civic and moral imperatives to solve. Across this history, economic advancement was predicated on environmental destruction: first, by eliminating the stewardship and use of the marsh by native peoples; then, projecting dreams of an imagined economy, by converting swamp to meadow; finally, by a growing city’s castoffs turning the marsh into its tailings pond. The next step in the trajectory of the Port Lands was positioned as a hybrid of economy and environment, much like the creation of Villiers Island. Filling the marsh would address two needs: one, to clean up an environmental nightmare, and two, to unlock its potential as new industrial land.

As political momentum built for the filling of the marsh, the most powerful supporters were deeply enmeshed in the city’s business elite. The health concerns of a 1,300-acre sewage pond, while important to the local government and residents, were secondary to the protection of capitalist interests. An 1887 letter to the city’s harbour master from Gooderham & Worts questioned the ability of their operations to continue given the conditions of the water—after a coal ship struck ground by its dock.23Desfor, 81. Soon, the broad strokes of a solution to the health and business concerns materialized. The Don River would play a critical role: by rerouting it into a wide, deep channel cut through the marsh, its flows could help to purge some of the pollution; dredging the channel and the nearby parts of the harbour would help accommodate larger ships, newly able to enter Lake Ontario with the 1899 dredging of the St. Lawrence River.24Desfor, 81-85.

Yet the most powerful motivation for the city’s business elite was the prospect of new land. Beginning in 1889, a variety of proposals to complete the Don’s rerouting and channel-cutting circulated; each also sought to seize the opportunity to fill in the marsh. One of the first would have had a private syndicate finance the water and filling work in exchange for a 45-year lease on the new land; it was vehemently supported by east-end councillors, including J. Knox Leslie, who held an interest in land with 1,300 feet of marsh frontage that would have greatly increased in value with the construction of the channel.25Desfor, 81-82. After much debate, the city council rejected these private overtures, choosing instead a cheaper 1892 plan (see Fig. 2, below) by city engineer E. H. Keating, rerouting the river into a 300-foot-wide channel (known now as the Keating Channel, which separates what will soon be Villiers Island in the Port Lands from Quayside on the waterfront).26Desfor, 84. Keating’s plan unsurprisingly included drawings of a filled-in marsh, but the city didn’t take any immediate actions to accomplish that goal.

In the following decades, the polluted conditions of the marsh slowly improved. Under serious pressure from citizens and the provincial government, the city forced Gooderham & Worts to start treating the manure from its feedlots in 1892, and secured permission to cut the breakwater for Keating’s channel, helping to flush the stagnant water further out into the lake.27Desfor, 83-86. By 1913, Toronto had built its first network of trunk sewers and treatment facilities, which helped to keep waste and sewage from spilling untreated into the marsh.28Desfor, 87. Despite its slow improvement, there does not appear to have been any movement to clean and restore the wetland. This likely reflects a combination of contemporary attitudes and technological realities.

First, as described earlier, wetlands in general were considered disease-bearing, unproductive spaces. Second, the serious legacies of contamination from all matter of wastes would likely have taken years of cleanup, in an era before governments made meaningful efforts to address environmental contamination, and potentially before technologies that enable site remediation today were widely available. But there was also an unchallenged assumption that the marsh would someday become economically productive land for private use by Europeans, with its roots in the earliest days of Toronto’s colonization.

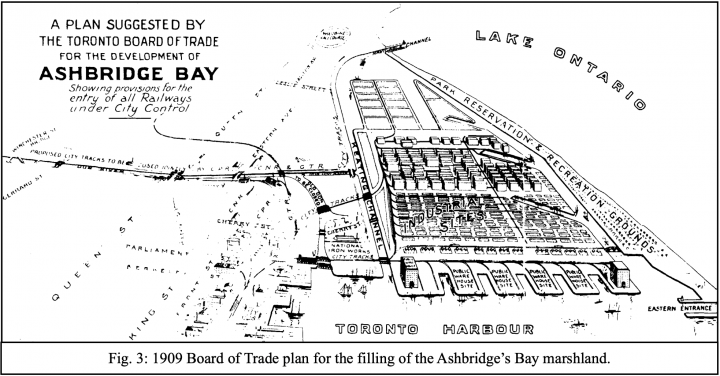

In the first two decades of the 19th century, Toronto’s capitalist forces drove the final nails into the heart of the struggling marsh. In 1906, the Ontario Association of Architects, integrated into the city’s development power structure, offered a plan that would fill the marsh and reserve the new land for manufacturing purposes. By 1907, the Canadian Pacific Railway and Grand Trunk Railway had both pursued plans to fill the marsh and control the created lands, which would be easily accessed by their lakeside trackage. In the end, a 1909 plan (see Fig. 3, below) from the Toronto Board of Trade—a civic organization funded by the city’s business community—became the foundation for the city’s actions.

The city went beyond the plan (see Fig. 4, below), filling most of the Keating Channel, forcing the Don’s flow west at a right angle into the harbour. By 1930, 1,000 acres of industrial land and 340 acres of parkland had risen from the former marsh.29Desfor, 87-88.

It wasn’t long before the Port Lands fell into disuse. The forced realignment of the river, and the elimination of the porous landscape of the marsh, left the lots closest to the Keating Channel vulnerable to flooding from the Don after storms.30“History of the Port Lands,” Waterfront Toronto, accessed December 7, 2018, https://portlandsto.ca/history-of-the-port-lands/.

Deindustrialization hit the city hard in the second half of the century, reducing demand for waterfront manufacturing land significantly. Today, the Port Lands are home to a mishmash of businesses and empty lots. Cherry Beach and the Leslie Spit, two parks that jut into the lake, provide a glimpse of the natural wonders of the lost marsh—a squawking colony of thousands of cormorants live in a forest on the shore of Tommy Thompson Park on the Spit, and small wetlands have grown around the margins of the new land. But they are disconnected from the city by hundreds of acres of mostly low-density industry, including a massive road salt storage facility for the city and a decommissioned power generating station, both of which have helped to contaminate the land.

In the past few decades, Toronto has undergone an astonishing transformation. The city has seen development on a mass scale, with tens of thousands of condo units added in towers all over the city and its suburbs. Corrected for inflation, home prices nearly tripled from 1997 to 2017, buoyed by the city’s economy and an influx of foreign investment.31Marisha Robinsky, “Real Estate Property Price Trend in Toronto,” Forest Hill Real Estate Inc., Brokerage, last modified January 9, 2018, https://www.torontohomes-for-sale.com/Toronto-average-real-estate-property-prices.html. Toronto’s economy has cultivated a wealthy, powerful, politically-connected developer network; the East Harbour project immediately north of the Port Lands (see Fig. 4), replacing a soap factory, is advertised as bringing 50,000 jobs in a “second downtown” for the city.32David Nickle, “Unilever Redevelopment Plans Offer Hope for Transit Infrastructure,” Toronto.com, June 6, 2018, https://www.toronto.com/opinion-story/8651654-unilever-redevelopment-plans-offer-hope-for-transit-infrastructure/. John Tory, the city’s current mayor, was first elected with a plan to build rail transit within the city—with a stop at the new development. After his election, John Duffy—the staffer who developed the transit plan—began working as a lobbyist for First Gulf, which owns the East Harbour site.33David Rider, “Gardiner Intersections: Developer First Gulf, its Lobbyists, the Mayor’s Office and a Poll,” The Toronto Star, June 10, 2015, https://www.thestar.com/news/city-hall-blog/2015/06/intersections-on-the-gardiner-developer-first-gulf-its-lobbyists-the-mayor-s-office-and-a-poll.html.

Given the city’s political context, the 2017 announcement of $1.25B in federal, provincial, and municipal funding to build Villiers Island, and make room for “Canada’s first climate-positive community,” was only surprising for its focus on its positive environmental impact.34“How the $1.2 Billion Dollar Injection Will Kickstart the Port Lands,” CBC News, June 30, 2017, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/toronto-port-lands-investment-1.4185524. The project is pitched as a flood protection feature for the Port Lands; its website notes that, in addition to bolstering the area’s defenses, it will reduce the vulnerability of East Harbour to flooding.35“Key Benefits of Flood Protection,” Waterfront Toronto, accessed December 7, 2018, https://portlandsto.ca/key-benefits-of-flood-protection/. But it will also unlock 54 acres of land on the island for new development.36“Villiers Island,” Waterfront Toronto, accessed December 7, 2018, https://www.waterfrontoronto.ca/nbe/portal/waterfront/Home/waterfronthome/projects/villiers+island/villiers+island.

Villiers Island is a vivid illustration of how economic advancement remains the main motivation behind Toronto’s plans for the Port Lands. It does provide flood protection—from a problem the city’s economic advancement created in the first place, and reinforced with the filling of the marsh. It will create a “climate-positive” community—on the site of what was once one of the largest wetlands in the region, a type of ecosystem with more carbon sequestration abilities than any built environment. It will host some affordable housing—in a city where developers have no requirement to, or interest in, integrating it into their projects. But most importantly, it gives the entrenched developer community a new project. As a bonus, it directly benefits the East Harbour project, owned by a developer with deep ties to the heart of the mayor’s office.

Less than an hour and a half’s drive southwest of Toronto, the Six Nations of the Grand River reserve is the largest in Canada. Much like the Ashbridge family’s original land grant, the reserve was created for Iroquois peoples who lived in New York and fought for the British during the American Revolution—on territory once home to the Mississaugas.37“The Haldimand Treaty of 1784,” Six Nations Council, accessed December 7, 2018, http://www.sixnations.ca/LandsResources/HaldProc.htm. Today—in 2018, in Canada—91% of the homes on the reserve are not connected to a water system. Communal taps residents rely on produce water that is too unhealthy to drink. And Nestlé, the enormous multinational corporation, pumps millions of litres of water for its bottling operations daily from the reserve’s land—paying royalty fees to the government of Ontario.38Alexandra Shimo, “While Nestlé Extracts Millions of Litres From Their Land, Residents Have No Drinking Water,” The Guardian, October 4, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/global/2018/oct/04/ontario-six-nations-nestle-running-water. That government uses those dollars to invest in places like the Port Lands, instead of supporting Indigenous residents without access to basic services. And so continues a colonial cycle of systemic violence that traces its beginnings to the first acts of Indigenous displacement and environmental destruction by Canada’s governments, focusing on the interests of the wealthiest at the expense of the poor, and the peoples who stewarded the land for centuries before European settlers had the chance to destroy it.

Works Cited

“Ashbridges Bay Park.” City of Toronto. Accessed December 7, 2018. https://www.toronto.ca/data/parks/prd/facilities/complex/1/index.html.

“Chronology of the Distillery Historic District.” Distillery District Heritage. Accessed December 7, 2018. http://www.distilleryheritage.com/PDFs/chronology.pdf.

“The Haldimand Treaty of 1784.” Six Nations Council. Accessed December 7, 2018. http://www.sixnations.ca/LandsResources/HaldProc.htm.

“History of the Port Lands.” Waterfront Toronto. Accessed December 7, 2018. https://portlandsto.ca/history-of-the-port-lands/.

“How the $1.2 Billion Dollar Injection Will Kickstart the Port Lands.” CBC News. June 30, 2017. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/toronto-port-lands-investment-1.4185524.

“Key Benefits of Flood Protection.” Waterfront Toronto. Accessed December 7, 2018. https://portlandsto.ca/key-benefits-of-flood-protection/.

“The Mississaugas.” Heritage Mississauga. Accessed December 7, 2018. http://heritagemississauga.com/the-mississaugas/.

“Sidewalk Toronto.” Sidewalk Labs. Accessed December 7, 2018. https://sidewalktoronto.ca/.

“Timeline: Ashbridge’s Bay.” Leslieville Historical Society. Accessed December 7, 2018. https://leslievillehistory.com/timeline-ashbridges-bay/.

“Toronto Purchase.” Mississaugas of the New Credit First Nation. Accessed December 7, 2018. http://mncfn.ca/about-mncfn/land-and-water-claims/toronto-purchase/.

“Villiers Island.” Waterfront Toronto. Accessed December 7, 2018. https://www.waterfrontoronto.ca/nbe/portal/waterfront/Home/waterfronthome/projects/villiers+island/villiers+island.

Bonnell, Jennifer. “Ashbridge’s Bay.” Don Valley Historical Mapping Project. Published 2009. Accessed December 7, 2018. https://maps.library.utoronto.ca/dvhmp/ashbridges-bay.html.

Desfor, Gene. “Planning Urban Waterfront Industrial Districts: Toronto’s Ashbridge’s Bay, 1889-1910.” Urban History Review 17, no. 2 (1988): 77-91.

Giblett, Rod. “A City ‘Set in Malarial Lakeside Swamps’: Toronto and Ashbridge’s Bay Marsh.” TOPIA: Canadian Journal of Cultural Studies 29 (2013): 105-124.

Hanes, Tracy. “Spirits Rising at the Old Distillery.” The Toronto Star, June 23, 2007. https://www.thestar.com/news/2007/06/23/spirits_rising_at_the_old_distillery.html.

Nickle, David. “Unilever Redevelopment Plans Offer Hope for Transit Infrastructure.” Toronto.com. June 6, 2018. https://www.toronto.com/opinion-story/8651654-unilever-redevelopment-plans-offer-hope-for-transit-infrastructure/.

Rider, David. “Gardiner Intersections: Developer First Gulf, its Lobbyists, the Mayor’s Office and a Poll.” The Toronto Star, June 10, 2015. https://www.thestar.com/news/city-hall-blog/2015/06/intersections-on-the-gardiner-developer-first-gulf-its-lobbyists-the-mayor-s-office-and-a-poll.html.

Rieti, John. “Toronto’s Port Lands Plan Includes Building a New Island.” CBC News. July 2, 2017. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/port-lands-development-1.4187182.

Roberts, Wayne. “Whose Land?” NOW Magazine, July 11, 2013. https://nowtoronto.com/news/whose-land/.

Robinsky, Marisha. “Real Estate Property Price Trend in Toronto.” Forest Hill Real Estate Inc., Brokerage. Last modified January 9, 2018. https://www.torontohomes-for-sale.com/Toronto-average-real-estate-property-prices.html.

Shimo, Alexandra. “While Nestlé Extracts Millions of Litres From Their Land, Residents Have No Drinking Water.” The Guardian, October 4, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/global/2018/oct/04/ontario-six-nations-nestle-running-water.